Nature of the Imagination

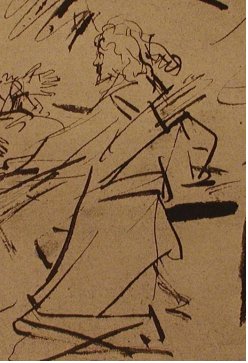

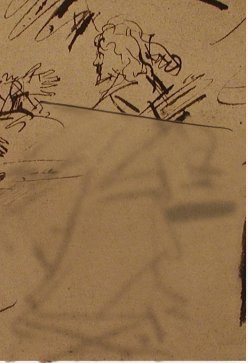

This drawing shows Rembrandt at his most feeble and at his greatest: Esau doesn't have the same substance as the Isaac. He is comparatively two dimensional. Isaac has all the three dimensional presence and subtle characterisation that one would expect from Rembrandt at the peak of his form. It must be the lesser quality of the Esau that has persuaded scholars to dismiss this as a copy after a lost original." However this doesn't explain how the copyist has made such a brilliant job of one figure and not of the other. May I offer another interpretation. This is one a of a series of Rembrandt drawings of the same group of models round a bed, at least five of which were made form approximately this view point. Others drawn from the other side of the bed that show Esau posing on that side of the bed (below) not as seen here.

If you now look again at the figure of Esau you will find that his body is insubstantial, though expressive, but his head is of the same quality, or nearly so, as the Isaac. A very plausible explanation of this schizoid quality is therefore that Rembrandt could have observed the head of Esau, but not the body because it was obstructed by the bed.

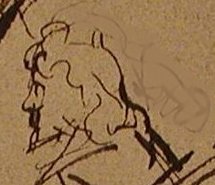

Look once more at Esau's head and you will see that it has been enlarged by Rembrandt to bring it forward in space by the addition of the outer line at the top back of his head. A smaller head is still completely visible within the larger.

If you are persuaded by my explanation this drawing becomes immensely important for the student of Rembrandt because it shows us on one sheet the huge difference in quality that we should expect between Rembrandt observing from life, and Rembrandt deprived of immediate visual reference. The same divide can be observed in countless other works by Rembrandt. I do not exaggerate we have lost half of the works previously attributed to Rembrandt precisely because today's scholars refuse to accept this dichotomy in his work. Yet Arnold Houbroken wrote: "Caravaggio would not attempt a single brushstroke without a living model before his eyes. Our great Rembrandt was of the same opinion and was indeed faithful to the principle that one must follow only nature. Anything else was worthless in his eyes. So where is the problem?