Life Drawing - The Male and Female Nudes: Lessons from Rembrandt

By Nigel Konstam

Contents

- Introduction

- Three Studies for an Etching

- The Activity of Drawing

- Shortcomings of Criticism

- Rembrandt's Female Models

- The Female Nudes Devastated

- Woman Seated on a Stool

- Conclusions

1. Introduction

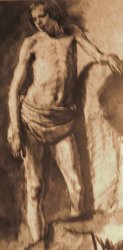

The drawing of a standing male nude by Rembrandt Pl.1 (B.710) was the single drawing to hang (in reproduction) in the principal's study when I was a student at Camberwell School of Art. He told me that he thought it was the greatest life drawing ever made. He found the juxtaposition of warm and cool passages rendered by two different chalks and two inks to be most painterly. As a sculptor, I find the forms and stance of the figure utterly convincing and characterful (and from this point of view I find it distinctly superior to Rembrandt's etching of the same model). The model has often been identified as Rembrandt's son, Titus. This magnificent drawing has recently joined the ranks of the rejected - 'once attributed to Rembrandt'. Click the thumbnail on the right to see a larger image.

Piecing together the information in the recent catalogues of the Drawings by Rembrandt and his Circle from the British Museum,The Rijksmuseum and the Boymans Museum, it becomes quite plain that the experts have been devastating the collection of life drawings once attributed to Rembrandt. When Mr Schatborn writes of Rembrandt's life drawings in his Rijksmuseum catalogue that "only very few can be assumed with any certainty to have been done by the artist himself", he is not exaggerating - he expects to be taken literally. Between them, the experts have devalued some of the most exquisite and touching drawings ever made.

Mr Royalton-Kisch (Keeper of drawings at the British Museum) responsible for the demotion of this drawing writes the elaborate technique of two chalks, brown and grey ink, heightened with white is "unparalleled in Rembrandt's certainly authentic works of the 1640's." However, No. 21 of his own catalogue (the African drummers c. 1638) mentions five media, Benesch's entry for the same drawing (B.365) also mentions a sixth: the use of a spot of oil colour. I suspect that the grey ink noted by Mr R-K. for (B.710) is in fact brown ink with white over the top, which would of course suggest that the media used for this drawing is less complex than Mr.R-K believes and more typical. The drawing has so many idiosyncratic marks in it which are typical of Rembrandt that Mr Royalton-Kisch is prepared to concede that Rembrandt may have had a hand in it (as a teacher putting in some heavy handed corrections). I think we can safely assume that had Rembrandt really come across this masterpiece among his students, he would have patted his brilliant disciple on the head and not waded in in this brutal fashion with his reed pen. This is Rembrandt correcting himself.

In this section I will attempt to explain why Rembrandt's drawings are so different from those of other old masters and why we must learn to accept the whole, broad range of quality found in his work if we are properly to understand the nature of his genius.

It seems to me that the experts desire to "purify" Rembrandt's works is enthusiasm misplaced. Firstly because Rembrandt clearly was not the kind of perfectionist they look for. Secondly because this policy of purification that has been relentlessly pursued for half a century or more has led to our losing sight of many interesting works from which we might learn a great deal about the art of drawing and the mind of genius.

The loss to Rembrandt is not merely numerical (at least 50% of the drawings accepted in 1900 have been demoted) he has also suffered a huge loss of stature. He has fallen from a state of grace into one of disgrace where he is frequently compared to Andy Warhol and others of the more commercial elements at work in art today. For instance, this from the Wall Street Journal - "Rembrandt van Rijn was a money changer in the Temple of Art.....he traded on his name with a single minded devotion worthy of a Julian Schnabel or a David Salle. Like them he knew what his name was worth and often attached it to the work of his students " etc. etc.

Rembrandt in fact signed or otherwise claimed only about 1% of his drawings. Those he did sign were drawn for autograph albums and therefore, did him less than justice, because they were drawn from imagination rather than life. He was also a prolific etcher and fortunately for us he made a practice of signing and dating his etchings. They form a body of authentic works to which the drawings can be compared.

2. Three Studies for an Etching

As a result of recent scholarship we are faced with three studies for a Rembrandt etching; all of very high quality and once accepted as Rembrandt's. We are now asked to believe they were done by unnamed students! Unnamed so far because no students work stands comparison with these drawings in quality - but watch young Raven, he is being groomed for stardom. He was fortunate enough to have written his name on the back of a recently discovered male nude study ( probably because he owned it. If he was claiming authorship he would surely have signed it on the front). Though the drawing Pl.8 is not outstanding it is almost certainly a Rembrandt. None of the other drawings, all once believed to be by Rembrandt but now attributed to Raven are so inscribed. Raven's paintings give not the least indication that he might be the author, quite the contrary!

Rembrandt's etching of two male nudes shows a standing figure in the same pose as the three drawings to the right. It is close in feeling to the drawings, one in Vienna, also once approved as a Rembrandt by Benesch B.709, and one in Paris A.55 demoted by Benesch but previously commonly accepted and B.710. The pose of the Paris drawing is virtually identical to the etching. All three drawings have been deattributed.

|

|

|

Left: Etching, Right: Drawing A.55 (Paris) |

|

|

B.709 (Vienna) |

B.710 |

3. The Activity of Drawing

If (B.710) is a Rembrandt, as I contend, it is not absolutely typical. It is unusual in two respects: it is much laboured over for a life drawing (we can guess it may have taken him 3 or 4 hours), and second, it is unusually good. My guess is that Rembrandt normally spent 20 minutes to an hour and a half on his life drawings. Furthermore, I would sometimes agree with Mr Royalton-Kisch that the results are "frankly indifferent" if not worse. However, the reasons for accepting that such undistinguished drawings are by Rembrandt are so strong on purely common sense grounds that I and the majority of previous critics have felt obliged to accept them.

To protect his reputation Michelangelo burnt the vast majority of his drawings. We may guess that Rembrandt was less vain, more accepting of his own human failure, or just more careless than Michelangelo. Most artists destroy a fair proportion of their drawings. One is sometimes quite surprised at the items that have escaped the fire in Rembrandt's case. Rembrandt was capable of being unbelievably determined in pursuit of the ideal expression (see for instance, Mr R-K's excellent notes on "The Lamentation at the Foot of the Cross", No.12), which often resulted in a work of extreme interest but little aesthetic appeal.. He was also capable of being splendidly descriptive and craftsman-like [as in the instance of the etching of the shell B.159] and also sublimely unmoved by other people's low opinion. Many of his contemporary critics complained that his work was "unfinished,...painted with a whitewash brush," etc. but his late style became yet broader. In a word, he was a variable genius. Genius is often unreliable, think of Shakespeare or Beethoven.

By refusing to accept the common sense point of view that the 3 drawings are studies for the etching, and by not allowing Rembrandt to take an exceptional amount of trouble in the case of B.710 , the experts are restricting the boundaries of his genius arbitrarily. Benesch is driven to the absurdity of having to suggest that Rembrandt copied his etching from "an excellent work of his pupil" in order to defend his own behaviour in deleting from Rembrandt's work a drawing that was "more descriptive and less vigorous" than was the norm.

It is widely recognised that Rembrandt's style as an etcher is almost always more descriptive and less vigorous than his style as a draughtsman. As Roger de Piles so aptly put it "his etchings do not have the breadth of vision present in the drawings". What could be more natural than going into his more descriptive mode, when he prepares for an etching. The rather laboured hatching of the drawing (A.55) prefigures the work done with the fine etcher's needle. [Benesch made another identical mistake with A.48.]

4. The Shortcomings of Criticism

If there has to be a starting point to the trail of disastrous judgements made by the 'experts' it would be here, in Benesch's refusal to accept less characteristic preparatory drawings for these two etchings It seems to have set a precedent in folly that others have willingly followed.

The most direct way of learning to read a drawing is by learning to draw oneself. Many experts have accepted the views of Benesch and his followers without question, but few have any real practical experience of drawing, (2000 hours of good instruction over a period of 5 years, plus once a week for life). Their judgement is little more than a balancing act between prevailing trends and opinions. From their writings, I get no sense whatever that they know how to read a drawing. One might have presumed that a specialist in Rembrandt was at the top of his profession, but as practised today Rembrandt studies survive in a state of endemic ignorance of the fundamentals of drawing,. They pass their misapprehensions from one generation to the next in an unbroken line. The experts are treading unquestioningly in the footsteps of their professor, destroying a vitally important artistic inheritance as they go. It is a scandal.

5. Rembrandt's Female Models

Judgements that go against the grain of logic and common-sense are accepted as if they did not exist. Pages quite recognisable from one of Rembrandt's own ledgers are now assigned to students, though they are clearly drawings of Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt's mistress. Mr R-K writes, "the anatomy of the female models with their swollen, oddly spherical stomachs (a pronounced feature of B.1142, 1143 & 1146) also bear no resemblance to Rembrandt's conception of the nude at any date whether drawn, painted or etched". (Mr.R.K's pronouncements become more authoritarian as the ground on which he stands turns to quick-sand).

|

|

|

|

B.1142 |

B.1143 |

B.1146 |

This is an outrageous statement in two respects: firstly, by suggesting that Rembrandt had a type-conception of the female nude when the main strength of his art rests on his refusal to be satisfied by a stereo-type. Rembrandt responds freshly and unpredictably to the individual in front of him A quality that is very important to the rest of us. Mr R-K shows himself to be oblivious to this quality. Secondly, the only thing that prevents this statement from being a down-right lie is the fact that Mr R-K and his friends - Schatborn of The Rijksmuseum, and Giltaj of Boymans Museum - have between them erased the evidence by deleting most of the drawings that answer to Mr. RK's description (drawings which a very well-founded scholarly tradition had accepted as by Rembrandt and of his mistress).

If these 'experts' do not care for the physical characteristics of Ms. Stoffels they share that distaste with Houbraken, who described Rembrandt's female nudes as "invariably repellent", and went on to say "one can only ask oneself with amazement how a man of such talent and intelligence could be so stubborn in his choice of models." This, from a contemporary of the master, would seem yet more reason for accepting such drawings rather than rejecting them. Had Mr R-K pronounced these drawings as typical, he would have been nearer to the truth.

There are in fact many examples in all media of Rembrandt's delight in round tummies, (pregnant or post-natal). Mr R-K need go no further than no.5 in his own catalogue, "Diana Bathing", and the related etching. There is a painting of Andromeda based on the same model in the Mauritshuis. "The Danae " in The Hermitage, or "The Bathsheba" in The Louvre, afford further examples from every period. Of the 20 or so drawings of female nudes allotted to the late period by Benesch, where the tummy is actually visible, all are round but one, (B.1115), probably the only one which is not of Hendrickje.

|

|

|

Diana Bathing |

Andromeda (Mauritshuis) |

Bathsheba (The Louvre) |

|

6. The Female Nudes Devastated

The drawing "Nude Surrounded by Drapery Beside a Bed" (B.1147) has been dismissed as "frankly indifferent" by today's keeper of drawings at the British Museum, (Mr Royalton-Kisch). Previous experts had accepted it as the preparatory drawing for Rembrandt's etching 'The Woman with the Arrow' B.202, for a very good reason. It is the same model in almost the same pose, this time on a bed. It is perfectly possible that the earlier experts would have also accepted Mr R-K's criticism without modifying their opinion that the drawing was nonetheless by Rembrandt. There are a surprising number of drawings which, either by the kind of association with incontestable work that we find here, or by their visual vocabulary or style, require Rembrandt's authorship, that could also be described as "frankly indifferent". In my opinion it is impossible that two separate artists, working independently from the same model, could have arrived at two images as close to one another as these . The description of the fall of light across the back for instance is virtually identical, allowing for the change of media.

|

B.1147 |

B.1146 |

B.202 Woman with the Arrow |

Rembrandt allowed himself a great deal of rope as an artist. He was able to suspend self-criticism to a remarkable degree and this was an important aspect of his creative vitality. There is a time for stringent self-criticism and a time to suspend criticism in any creative project. The artist has to be prepared to act and see what happens with no guarantee of the outcome. Rembrandt, perhaps the most creative of all artists, has more to teach us about acceptance (one does not hit the bulls-eye every time), than any other. These two aspects of his personality: the highly creative and the ability to suspend self-criticism, are not disconnected. If we allow the present blinkered approach to Rembrandt to go unchecked, this imperfect, free-wheeling side of his genius will be hidden. With this approach we will lose sight of what he has to teach us about creativity as well as more than half his life's work! We cannot afford to allow either of these things to happen. There was only one Rembrandt and we do not want his creative personality transformed for us by the narrow-minded 'experts' of today.

B.1147 is one of a pair of drawings of the same model, in the same pose, drawn by the same hand with the same pen, brush and ink. The other is in the Rijksmuseum. Both were accepted as by Rembrandt; both have recently been assigned to Johannes Raven. Both bear far greater resemblance to the Rembrandt etching and to Rembrandt's drawing style than they do to the single drawing supposedly by Raven put up for comparison. This sole example of Ravens draughtsmanship is absurdly doubtful. (see caption Pl.8 ).

Many of Rembrandt's late life drawings, paintings and etchings are believed to be based on his mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels, and there are a number of reasons why we should believe this to be true. Allowing for the variations attributable to pregnancy, birth (in 1654), post-natal recuperation, illness and death (in 1661), she exhibits the same general physical type and roughly the same hair style in many works. (The fact that her facial features are not always consistent should not worry us; neither were Saskia's in Rembrandt's work). Rembrandt was declared insolvent in 1656. We can therefore assume the massive use of models which was otherwise the norm in his studio came to an end through lack of funds and lack of space in his new surroundings. Knowing of his belief "that one must follow only nature,....anything else was worthless in his eyes"(Houbraken), it would seem natural for him to retire into a more private world and draw from his mistress ( perhaps rather less natural, to call young Raven into his bedroom on such occasions for drawing instruction).

Seated Nude with Arms Supported by a Sling (B.1146) Houbraken may have had a drawing such as this in front of him when he wrote of Rembrandt's female nudes; "he produced such pitiful things that they are hardly worth mentioning". Houbraken was no fool, as was shown by his lively and acute appreciation of other aspects of Rembrandt's work. He was a fellow artist and an Amsterdamer who knew many of Rembrandt's students. He might have known the master himself. If he could be so forthright in his published criticism we can assume that it was probably a consensus view and there was some truth in it. Even after the recent scholarly massaging of the facts, one has to admit there is something in it. Yet 350 years after the event, present day experts have no qualms in dismissing this work on the grounds that it simply is not good enough.

B.1146 and the previous drawing, B.1147 are linked to Rembrandt by incontestable common sense arguments; that is, this is the same model in the same pose as the previous drawing, obviously by the same hand on the same occasion. Other than the quality, there is absolutely no reason to doubt that they are the preliminary sketches for the etching. I am calling the 'experts' to account for their failure to bow to the overwhelming evidence.

- The evidence of the style and character of the drawings;

- Evidence that the model is almost certainly the artist's mistress;

- Evidence that she is in the same pose as in the etching,

- The documentary evidence from Houbraken which should predispose us to accept such "indifferent" drawings as this, evidence which most previous scholars have accepted.

B.1147 (detail) The arm in this rejected drawing is very much more sensitive than in Rembrandt's etching.

There are also two pieces of purely practical evidence - all three works show that a sling was used to support the model's arms (something that Rembrandt did frequently). In the etching the sling is transformed. The British Museum drawing (B.1147) reduces the sling to a white streak above her hand which has no function. This streak was then finally converted into an arrow according to some, or a chink of light between the curtains according to others, in the etching. This evidence, plus the steady transformation of the sling should be more than enough to persuade us that these drawings are by Rembrandt. Furthermore, they were drawn on Rembrandt's ledger paper! A paper that is easily recognisable by its ruled margins and which Rembrandt used on several other occasions. The experts' view leaves us to wonder if Raven helped himself, or received the paper as a gift!

We can defend the quality of these drawings. They may not be attractive but I would not go so far as Houbraken. My first reaction was not so dissimilar to his. Surely her head is too big, her thighs too short and her calves too long. but when we have accepted these defects, we can acknowledge that as a drawing of a plump, soft lady of a certain age, it is rather a success. The forms of the torso particularly are a splendidly tactile mass. If we were told it was a Rouault, for example, we would have no difficulty in accepting it, and Rouault was one of the greats of the 20th century, whose ability to transmit the tactile values of the nude to paper was extraordinary. Is Rembrandt's sin that his ambitions were too far ahead of his time?

|

B.1147 |

B.202 Rembrandt's etching Woman with the Arrow |

B.1147 is so close to the etching B.202 'The Woman with the Arrow' (signed and dated 1661) that a direct comparison is profitable. The etching is immediately appealing (to me, if not to Houbraken). I love the way the light skims across the forms of the back, modelling it beautifully. I also admire the way the upper foot twines around the ankle; but there are some shocks to accept as well. What about that hand, for instance - it's a shame. Rembrandt tinkered around with this plate. Even after six proofs he somehow failed to rectify that hand. In truth, the whole arm is not much better - it is wooden and fails to articulate at the elbow and shoulder. That hand is not really holding an arrow, nor is it closing the curtains; it has a long way to go back before it even makes contact with them. Do you see how the sling still leaves its mark on the wrist? Maybe we could account for that hand by looking back at 1146 to see how the hand is pushed out of place by the sling. Rembrandt could not see it - could not/would not draw it. We can learn a lot about Rembrandt by seeing these works as a group.

If we examine these problem areas in the drawing and compare them with the etching (which is undoubtedly Rembrandt's work) we find the hand is less offensive and the arm is considerably better articulated in the drawing. In the torso, the volumes and movement up to the head are better than in the etching. You may have to be a bit of a draughtsman yourself to see that the front silhouette of the breast, and the wrinkles below in the etching, do not read with the plane of the back. This is because they are spatially wrong. The shadows give a beautiful relief across the back. They almost persuade us that there is room for the depth of the rib-cage, but there is not. Even compared to one of Rembrandt's most successful etchings, this drawing does not come off too badly. One would be wise to judge Rembrandt positively - by his successes, or he disappears as a result of a thousand pin pricks.

Another casualty by association with these is B.1145, a truly lovely drawing, again of Hendrickje, with her round belly etc. Mr. R-K finds the exquisite chiaroscuro to have a "contrary logic". I see only logic. Perhaps Mr. R-K was confused by the shadow of an object outside the picture cast on the floor and on the two legs of the chair to the left. If I could choose one drawing to represent the spirit of Rembrandt's life drawings it would be this. At one level it is mundane: a poor tired woman propped up with slings and chairs for the artist to draw. However, through the light and the incredibly subtle balance plus the rhythm of the whole, it becomes a figure of resurrection.

Rembrandt was an explorer, not a manufacturer of smart art objects for the Times/Sotheby's index. Many present day artists have followed his example in his refusal to bow to other people's values. It is one of the reasons why we love and respect him so much. We cannot allow him to be 'normalized'.

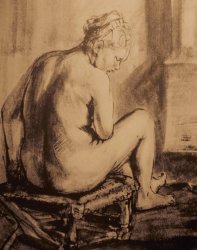

7. Woman Seated on a Stool

A fitting climax to this litany of tragedies is the case of two outstandingly beautiful drawings - both previously attributed to Rembrandt. Both clearly of his mistress, Hendrikje Stoffels, seated on the same stool and in the same pose. These drawings are compared in the Rijksmuseum catalogue. Schatborn accepts that "at first sight the drawings resemble one another very closely - the nearly identical position of the two figures on the surface of the page - the use of the same ink, lines that do not describe with precision and transparent touches of watercolour". They are indeed so identical in feeling, in materials and treatment that it is impossible to doubt that Rembrandt did them both probably at the same session. Yet Mr. Schatborn accepts one B.1122 and not the other (B.1121).

|

B.1122 |

B.1121 |

A real ability to draw is rare. It develops as a result of an ability to see the subject as a whole, disposed in space with precision. Giacometti, one of the great draughtsmen of the 20th century, for instance, usually arrived at his final statement as the result of a long process of adjustments often taking many sittings. He is a draughtsman as a result of knowing where he wanted to go and having the stamina to make the journey. His chosen media were pencil and rubber or oil colour both of which allow for a great deal of adjustment. Rembrandt was uniquely gifted insofar as he was able to arrive at a firm space structure often with remarkably few adjustments. Both these drawings are splendid examples; I use then in lectures to demonstrate how drawings are built. Of the two B.1121 is more attractive with its dazzling play of light and, I think, the more successful as structure.

The pose is like a sculpture carved in a block . Her back and her left forearm lie in the back plane and her entire right leg , upper arm and head lie in the plane of the side of the block - the stool, rickety as it is, emphasises the coordinates of the block. Every mark, however casual seeming, contributes to creating forms that move with wonderful precision within the block. It would be possible to reconstruct the physical presence of Hendrickje in sculpture from these two drawings. This kind of miracle happens to very few artists. Yet the 'experts' are prepared to attribute such clarity to second rate students who happened to have passed through Rembrandt's studio.

Even for Rembrandt it did not come right first time. One can see how he has adjusted the position of the left buttock of B.1121 four times and how the head is sketched in two different positions. It is my opinion that Rembrandt never quite decided which he preferred, it is still open to the spectator to choose. In the second drawing B.1122 the head has swung round and dropped to the lower position so that her forehead touches the side plane of the block. Here Rembrandt has adjusted her buttock and her left shoulder. As a structure it is not one hundred percent successful. I find a discrepancy between the front plane of the chest and the planes of the shoulder and back: they do not quite hang together. If we see that much of the back would we see the front plane nearly head on? Both demonstrate incredible virtuosity in the placing of the marks but the marks themselves have none of the usual virtuoso's vanity about them one might find in a Van Dyck. There is an everyday feeling about them. You or I might have used such marks in writing.

These are two great drawings; one an unmistakable bulls-eye, the other a near miss. According to the 'experts' the bulls-eye is now by Aert de Gelder (not a man previously known for his draughtsmanship) and the near miss is a Rembrandt. The mind boggles, how can the art of drawing survive such reversals?

To get any idea of why the 'experts' have chosen to give the greater of the two to Aert de Gelder we have to resort to Giltaij's new catalogue of the Boymans Museum's Rembrandts (reduced by over 50% on Benesch's 1954 catalogue). We find in the catalogue that Giltaij finds the stool "incoherent.... while the modelling of the back gives the impression of being over detailed and cautious ... the contours (of the figure) are weak and hesitant"! Maybe the cause of this appalling misjudgement is that in this case Rembrandt got to his goal before he needed to use those "bold strokes " so beloved by the experts.

Schatborn, writing of this drawing and another pair of similar drawings says "The fact that there were models in both groups (of drawings) who were drawn by Rembrandt in the same pose strengthens the attribution to de Gelder and Raven"! Schatborn's idea that it is 'unlikely' that Rembrandt would have drawn the same model in the same pose from a different viewpoint is contrary to both experience and common sense. No wonder Schatborn has written of Rembrandt's other life-drawings "only very few can be assumed with any certainty to have been done by the artist himself". Following his methodology and logic there will be no more Rembrandt drawings at all.

8. Conclusions

The lack of feeling for the masterpieces that these men have chosen to demote, the sheer ineptitude of choosing to describe Rembrandt's drawing style as "using lines that do not describe with precision," is hardly the way to describe what I have chosen to call "casual seeming lines" . Rembrandt's greatness as a draughtsman depends on the precision with which the planes that those "casual seeming lines" clearly define. Those planes stack together to create precise volumes in space. Such crude, insensitive, judgements, should debar these 'experts' from any employment requiring feeling. Schatborn has been promoted to serve on the committee of the Rembrandt Research Project!

What we learn from Rembrandt clearly depends on which works we accept as his and how we interpret them. My interpretation shows Rembrandt to be a man, humble in the face of nature and yet so confident of his own enduring greatness that he did not bother to tidy away those works that did him less than justice. One feels that Rembrandt cared more for truth than for his own reputation. He did not hesitate to use any odd scrap of paper, newspaper, ledger paper or the back of an invitation for his drawings. They were his private concern, he did not see them as objects of commerce.

He put his confidence in the truth as he saw it and in the good sense and sensibility of those who could share his vision. A vision that is so individual both in its subject matter and in the means of expression that he rarely felt it necessary to put his name to it. He showed a trust that was justified until recent times. If an enthusiasm for Rembrandt has always been a minority interest, it has always been a sizeable minority among artists.

I see a Rembrandt who was immensely able but who did not feel it necessary to show off his ability on all occasions. A man who was prepared to pursue his vision at whatever cost to the work in hand with scissors and glue, with bold strokes or whatever else he could improvise to serve his needs. Little wonder that so many artists of the 20th century have paid him tribute: Picasso, Rouault, Bomberg through to Auerbach, Kossoff and countless others in our day. It is the 'experts' who grossly misjudge him. We must find new experts.

How disappointed Rembrandt would feel that those who have spent so much time studying him have ended up with so cramped and pernickety a vision.

There may be many who share the experts incredulity that an artist of the capacity of Rembrandt should leave behind a good number of works that are "indifferent "or even "repulsive". There may be many who wish he had not - who at least feel that they damage his reputation. I suggest another way of looking at these uncomfortable facts.

I believe the importance of Rembrandt's contribution has little to do with the number of outright masterpieces that he amassed during his long career. His reputation rests above all on the new direction he took and the new, explorative attitude he developed towards his art. I think we are missing the point if we see him only as an individualist who did not give tuppence for other people's opinion (though he was that also). He knew where he was going artistically. As a matter of principal, he was firmly turning his back on beauty in the sense of the accepted norms of classical art, he was responding to life as he saw it - thoroughly accepting that it was not always beautiful. Many of his early etchings of the female nude (Diana) go out of their way to shock or repel. His early work "The Deposition" sails close enough to Rubens' composition to make the point that he, Rembrandt shuns such heroics and will give us the human tragedy in all its undignified detail. It is unlikely that Rembrandt would have gone along with Keats' muddled adage that "Truth is beauty and beauty truth". Rembrandt nails his colours firmly to truth at any price. His artistic personality had rough edges and should remain that way. To tidy Rembrandt is to falsify the character of a guru for artists. His reputation has plummeted. It has done us all great harm.